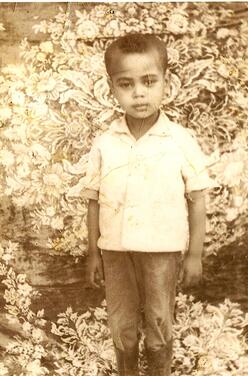

Ethiopian refugee Tefere Gebre was just 15 years old when he arrived in the United States—starting over in a new world alone, without any family by his side.

Over 30 years later, he is executive vice president of the AFL-CIO—the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, the largest labor union in the world, representing over 12 million Americans. Gebre is the first refugee elected as a national officer of the organization.

Gebre was still a boy when he was forced to flee Ethiopia, a country that suffered political turmoil and famine during the 1980s. “People were getting murdered on the streets by the government,” Gebre says. “They were just grabbing kids and torturing them if they were suspected of being an anarchist or aiding the opposition. That's when I knew I had to find a way to get out.”

People were getting murdered on the streets... That's when I knew I had to find a way to get out.

In 1982, Gebre and four friends managed to escape to a refugee camp in neighboring Sudan, walking through the desert for 93 days. There they applied to enter the U.S. through the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNCHR), taking several written and oral exams in the vetting process.

“When the UNCHR announces who has been accepted to resettle to the U.S., they post the names outside their office,” says Gebre, recalling the jostling crowd pressing against him as he searched the list. “That was like another birth for me, when I saw my name there.” His four friends did not make the cut.

But Gebre didn’t have any family members in America, and he needed a sponsor to support his relocation. His mother remained in Ethiopia. His brother, who had lived in the U.S., had died in a car accident.

That’s when the International Rescue Committee stepped in to help. Currently operating in 27 U.S. cities, the IRC supports newly arrived refugees by providing immediate aid, including food, housing and medical attention.

“I was received in New York by an IRC staff member,” Gebre says. “Then they put me on a plane to Los Angeles and an Ethiopian man who worked at the IRC met me at the airport.”

IRC staff members helped Gebre and three other Ethiopian refugees apply for driver’s licenses, fill out I-9 forms for employment, and complete tuberculosis tests. They helped them move into an apartment (which the IRC sponsors until new arrivals find work), and took them to apply for public benefits. Later, the IRC acted as Gebre’s guardian so he could enroll in L.A.’s Belmont High School.

“There was no way anybody of my status could survive all of that without the IRC being there,” Gebre says.

The IRC continued to act as a lifeline for Gebre in coming years, helping him reconnect with his family in Ethiopia. “I sponsored my mom to come to the U.S.,” he says, “and I did that through the IRC.”

Gebre went on to attend California State Polytechnic University on a scholarship. During his sophomore year, he took a night job loading UPS trucks so he could send money to friends still in Sudan. There he joined his first union—the Teamsters —another turning point in his life.

“The fact that someone was looking after me, that there were real work rules—that I knew what my responsibilities were and what my company's responsibilities were—I thought everybody should have that,” Gebre says. “Ever since, I have really committed myself to advancing that cause.”

While attending graduate school at the University of Southern California, Gebre became a legislative aide for Willie Brown Jr., speaker of the California State Assembly. He then embraced an even bigger challenge—to become the executive director of the Orange County Labor Federation.

“I did that because Orange County is the most conservative part of the state,” he says. “As a skinny Ethiopian refugee, I wanted to prove myself by organizing Orange County. And I did.”

While working in Orange County, he found that there were hundreds of sanitation workers sorting trash eight hours a day at minimum wage. They didn’t have a union to represent them. Gebre learned that they had tried to organize but the sanitation company called ICE and had those who were undocumented deported.

“I really couldn’t sleep,” Gebre recalls. “What were we doing if we couldn’t help these people?”

He gathered church leaders, community organizers, and local Teamsters to speak with the company about establishing a union for the workers.

“Seven months later, people who never had health care, people who lived under the threat of deportation, people who got one bottle of water a day while working in the Southern California heat, they overwhelmingly voted to join the union,” Gebre says.

Today, the workers receive two weeks of vacation and health care for themselves and their households, and enjoy wages equivalent to double what they made before the union.

“Making that change happen is the biggest accomplishment in my life,” Gebre says.

His work caught the attention of the AFL-CIO. He was elected executive vice present in 2013, breaking ground for refugees in the U.S.

“Refugees really are a select group of people with a different drive than the population at large,” Gebre says. “It is not that easy to leave your village and your country, and abandon everything you know—even when your life is threatened. Once we come to the U.S., we are driven to make something out of our lives.”

The United States cannot afford not to have refugees.

Gebre also recognizes that America has a special appeal for refugees everywhere, despite recent changes in U.S. policy that have put severe restrictions on immigration.

“If the United States of America is not the leading place for the protection and resettlement of refugees, I don't know what country would be, because we're built by immigrants and refugees,” he says. “I think all of us—refugees and refugee advocacy organizations—we have a lot to do now. We have to educate the American public about what to think of when they think of refugees.”

He notes that Albert Einstein—one of the founders of the IRC—was a refugee.

“The United States cannot afford not to have refugees,” he says. “There is no reason why the next child refugee cannot become the next CEO of Apple, cannot become the next senator, cannot became the best mother of the next great scientist in this country. Impossible is nothing in this country if we work together.”