Coming to America: the reality of resettlement

“The vetting is so extreme, there is no room to lie—you will get caught,” say Azzam and Nisreen Tlas, Syrians resettled in San Diego who have experienced the four-year process.

“The vetting is so extreme, there is no room to lie—you will get caught,” say Azzam and Nisreen Tlas, Syrians resettled in San Diego who have experienced the four-year process.

The Trump Administration’s travel ban has led to confusion and fear for countless people wondering if they will be allowed to start a new life in the United States, as well as for families already in America waiting for loved ones to join them.

For now, the fate of these innocent families rests with U.S. courts following a March 15 ruling that blocked President Trump’s second executive order to suspend refugee admissions.

The U.S. resettlement program is regarded as the world’s most successful and secure, a process that is already “extreme”—loaded with safeguards that include interviews where refugees are asked to relive the worst experiences of their lives. It’s an enormously selective program with multiple layers of security checks.

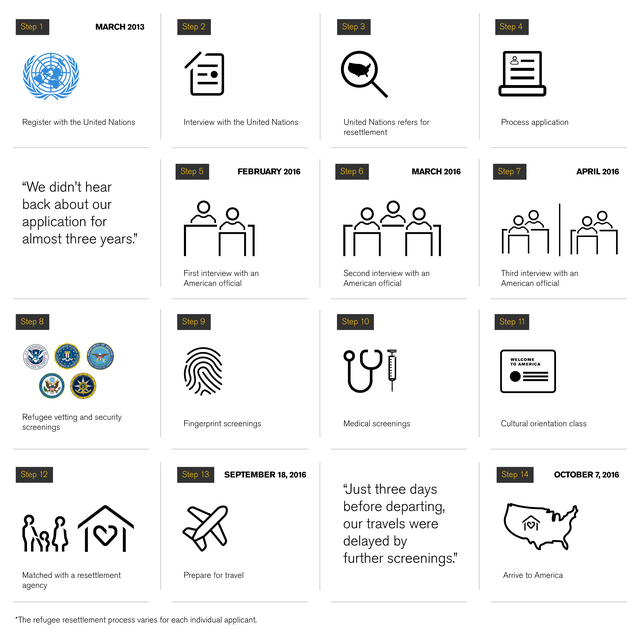

Below, we trace the saga of the Tlas family—Azzam, 43, his wife, Nisreen, 33, and their four young children—refugees from Syria who spent four years in Jordan before being resettled by the International Rescue Committee in San Diego. Their vetting process consisted of 14 steps.

The United Nations agency for refugees determines if an individual qualifies as a refugee—someone who has been forced to flee his or her home country due to war, persecution or natural disaster.

We used to live a comfortable life in Homs with our children, but then the war started in 2011. The security situation became deadly for us. We were terrified for our children. We only wanted to save our children. We initially fled to Damascus, but could stay only for 10 months. On Dec. 25, 2012—Christmas day—we packed into a car and drove to Jordan, which took three days. It normally takes only two hours, but there were so many people leaving it took longer.

—Nisreen Tlas

A stray bullet hit me on the side of my stomach. I was afraid to go to a government-run hospital even though I would be able to get free medical care—the bullet would cause suspicion that I was fighting. So I went to a private hospital instead and paid out of my pocket. When I was discharged, we felt we were no longer safe and had to flee.

—Azzam Tlas

A U.N. official identifies whether to refer the individual to the U.S. or to another country for resettlement. UNHCR collects identifying documents, biographic information, and biometric data (such as iris scans).

We had an interview where we were asked mostly general information: why we had to leave Syria, who in our family was left in Syria, why did we come to Jordan, what do we plan to do here. Then, they took our photos. It’s seemed like a simple process.

—Azzam Tlas

The U.N., a U.S. embassy, or another agency handpick only the most vulnerable refugees for potential refugee resettlement—out of more than 65 million refugees worldwide, about 0.1 percent were resettled to the U.S. last year.

We found refuge in Jordan, but refugees have no life there: we can’t work; we are deprived basic human rights. We weren’t seen as equals; we were second-class citizens. We only received $164 a month for food—this wasn’t enough for six people. We were told there was a chance to go to America for a better life, so we went to the United Nations and applied for resettlement.

—Azzam Tlas

U.N. officials send all identifying documents and other biographical information to one of nine federally funded resettlement support centers (like the ones run by the IRC in Thailand and Malaysia). The centers, located around the world and closely monitored by the State Department, help refugees and their families prepare their cases for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). They compile the required personal data and background information for security clearance.

The Tlas family did not hear back from the center or the DHS for almost three years.

Those three years were so hard for my family. We lost hope. My children didn’t live like the rest of the kids in Jordan. I wasn’t allowed to work and so was unable to feed my family; the food and cash assistance we received was not enough to meet our basic needs. To be honest, it was the toughest time I’ve ever experienced in my life. I felt any second we could be sent back to Syria. We lost hope.

—Azzam Tlas

At this point, U.S. immigration, security and intelligence officers have a stack of information about the refugees being vetted. The Tlas family would undergo a total of three interviews in the span of three months.

We were, again, asked very general information: why we want to go to America, why were we in Jordan, what is the situation in Jordan like for us, did we still have any family in Syria. It was very detailed; very thorough. They were the same questions asked in different ways.

They asked us about the specifics of our journey. They cross-referenced everything we told them to make sure we were telling them the truth.

I was interviewed separately from my wife. The person interviewing me was very interested in my brother: where was he, where was he working. But we didn’t know. I was asked if he was politically active in Syria. They were very persistent about him, but we hadn’t been able to keep in touch since I left Syria.

—Azzam Tlas

My husband and I were interviewed together. They asked us about specific people: if we knew who they were, our relationship, whether they were political activists. We knew “of” them, but didn’t “know” them. We weren’t in contact and had never met them. They kept asking us this same question. It was exhausting, but we told the truth.

—Nisreen Tlas

By the third interview, we were tired and again they asked about my brother. We could do nothing but tell them the truth. I didn’t understand why they wouldn’t believe us. Why would we lie? Even if we tried to hide anything, they would eventually find out. We couldn’t risk lying; there is no room to lie.

—Azzam Tlas

During this entire process, biographic security checks were underway with U.S. security agencies including the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), DHS, and State Department. Syrian refugees may be flagged for additional security screening.

The family’s fingerprints are screened against various biometric databases, including those maintained by the FBI and DHS, which contain watch lists.

Once approved for resettlement, all applicants, including children, are required to undergo medical screenings conducted by the International Organization for Migration or by a physician designated by the U.S. embassy.

Cultural orientation classes range in length from three hours to several days. Classes educate refugees on American customs, laws, health benefits, as well as what to expect in the initial resettlement phase.

Refugees are matched with one of nine domestic resettlement agencies, including the IRC, that provide critical services for refugees coming to the U.S.

Before refugees coming to the U.S. leave the countries where they temporarily reside, they sign promissory notes agreeing to reimburse the U.S. government for travel costs.

Just three days before departing, the Tlas family’s trip was delayed by further screenings.

We finally received a letter of acceptance. It said “Congratulations, you’ve been accepted. Pack your bags, you’ll be leaving soon.”

Our flight for Maryland was scheduled for Sept. 18.

Three days before departing, the agency called and said our departure was delayed. At this point, we were completely packed and ready to go. We had already handed our house keys back to the landlord.

We waited for 15 days not knowing what was going to happen. We didn’t have a house; we were now stuck. Where were we supposed to go with the kids? We were told to figure it out and they’ll get back to us when they can.

We resorted to calling friends of friends and moved from house to house for 20 days until we got a call—our paperwork was finished and we were rescheduled to go to California.

—Nisreen Tlas

Upon arrival at a U.S. airport, an immigration officer reviews the refugee’s paperwork and conducts additional security checks. For the first 90 days, resettlement agencies like the IRC work with state and local governments and community organizations to help new arrivals settle into their communities.

The security check is very tight. We understand why America wants to make it harder; it’s the country’s right to keep people safe. But I don’t think it can get harder. You cannot lie your way through this process, you cannot hide, you will get caught.

America is so different from Jordan; I can move forward with my life. We felt like a weight was lifted off our shoulders. We felt like we were finally in a democratic country, land of freedom. It’s a beautiful country—a country that respects individuals.

There are a lot of things that are extremely different for us, but it’s our second life. It’s hard to believe that we survived.

—Azzam Tlas

The Tlas family has been in San Diego for five months (as of March 2017). The IRC enrolled Azaam and Nisreen in English classes and their children in school. Azam has secured a job at a market in El Cajon and a driver’s license, also with the help of the IRC.

We hope to improve our language skills and get an at-home child-care license to start our own day-care business. We left hell for heaven. Here, our rights are honored like any American citizen. There’s stability for us and our kids.

We are waiting for my brother and his family. We were called regarding his resettlement application. I’m now worried about them given the situation in America.

—Nisreen Tlas

Update, May 8, 2017: The Trump Administration "travel ban," which would suspend refugee arrivals, is facing new scrutiny in two federal courts: The ban would separate families, put more vulnerable people in harm’s way, and would not make the country safer. We'll post the latest developments on our Refugees in America page.