Alone in Azraq: A Syrian teenager's story

Fifteen-year-old Samir became separated from his family after his home in Aleppo was attacked. He tells us about his journey to Jordan and hopes to be reunited with his parents.

Fifteen-year-old Samir became separated from his family after his home in Aleppo was attacked. He tells us about his journey to Jordan and hopes to be reunited with his parents.

On a warm Thursday morning, we begin our journey east from Amman into the empty desert. It isn’t long before we see the first of thousands of white caravans reflecting the merciless sun; we have reached the sprawling Azraq refugee camp in northern Jordan —home to more than 20,000 Syrian refugees fleeing their country's ongoing civil war.

Beyond the checkpoint and the wire fence, Syrian children who arrived in the camp on their own lie about on a patch of dried grass, kick around a ball, or huddle inside their makeshift homes chatting. “Marhaba” I say in greeting as I bend to sit with a group of young boys on the turf; an overhanging metal roof shields us from the hot sun.

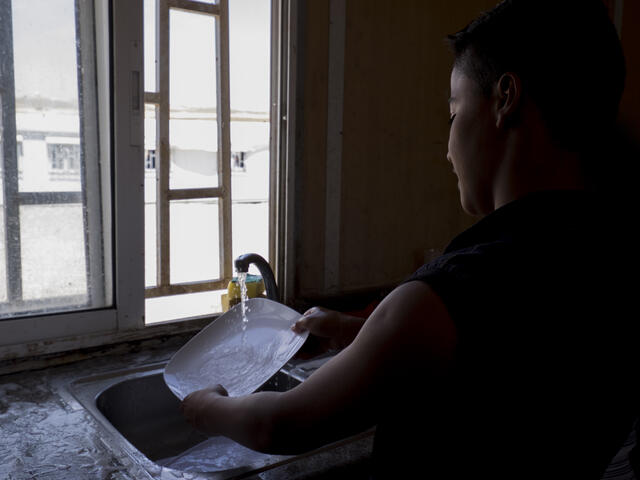

Among them is a young man, an adolescent really, his dark eyes projecting the profound misery that had turned his world upside-down. He has styled his thick hair with gel and wears a faint moustache. I introduce myself, and he tells me his name is Samir.* He is 15 years old and alone.

Samir and I head to a recreation room in one of the many caravans and find two chairs next to a foosball table. We sit opposite each other and he begins to share the stories behind those sad eyes.

One of 15 children, he was separated from his family nearly four months ago after his town of Aleppo in northern Syria was bombarded with missiles. Samir was visiting his uncle, just a few miles away from home, but by the time he was able to return, his entire family had disappeared.

“Our house was hit, but was not completely destroyed, thank God,” he recalls. “I stayed there alone for 15 days waiting for my family. No one knew whether they were dead or alive.”

Samir's aunt convinced him that Syria was no longer safe and that he should seek refuge in neighboring Jordan. He made his way from Aleppo with others seeking safety to a barren piece of desert known as “the berm,” a no man’s land where 30,000 people were camped near the border, hoping to be allowed to cross. Samir waited at the berm for 20 days before crossing.

Gazing past me as he speaks, as though he were seeing “the berm” once again, he continues:

“There were thousands of people at the berm—a lot of families and a lot of sick people. Organizations gave them tents, blankets, water, food. Everything is available, but people have to wait in turn. People don’t interact with one another; everyone is for himself there.”

Unaccompanied minors like Samir—along with other vulnerable refugees, such as pregnant women, the sick and the elderly—are given priority to enter the Azraq refugee camp in northern Jordan, where they are welcomed by aid organizations.

When Samir crossed the border, he was put on a bus and driven to Azraq, where he was immediately referred to the International Rescue Committee’s child protection team. IRC aid workers provided Samir with a safe place to stay and food to eat, and asked him questions to help them reconnect him with his family.

The team of some 64 aid workers—which includes 36 Syrian volunteers who are refugees themselves—is on hand 24 hours a day, seven days a week to welcome and care for unaccompanied and separated children, try to locate their relatives and, if necessary, identify potential foster parents. More than 3,000 such children have crossed into Jordan since 2012. An estimated 94 percent have been reunited with their families, but the process can be daunting and tedious.

The IRC team was able to quickly track down distant relatives of Samir’s in Azraq, but because they did not have documentation that proved their relationship, Samir could not be released to them.

Then, one month later, Samir’s immediate family found him using WhatsApp, a mobile messaging service. They were all alive and had returned to their home in Aleppo.

Tears well in Samir’s eyes as he finishes his story. “My family tells me that the bombings and air strikes continue,” he says. “They are in a bad situation, it makes me cry. They don’t even have money to buy bread.”

It’s been a few weeks since Samir last spoke with them. Internet access has been cut off in their town.

“His family have to walk two miles to get a phone signal, so whenever they call, even if it’s the middle of the night, we will rush to wake up Samir so he can speak to them,” says Salman Amer, the IRC child protection caseworker looking after Samir in Azraq.

Uncertainty is difficult for anyone, especially a teenager who has already had to deal with the trauma of conflict and violence. I ask Samir about his 14 siblings, astonished that he has so many brothers and sisters. He smiles. “My dad married three women. I have older siblings, some of them are married.”

Samir’s father recently traveled to the border in hopes of being reunited with his son. But as of March, Jordan is allowing only 100 refugees into the country a day. Although anxious to be with his family again, Samir is concerned about his father’s welfare.

“My dad went to the berm alone to bring me back. And now he’s just waiting and we don’t know when he’ll be able to cross.”

As he waits, Samir helps out at the camp reception center by doing small chores and spends his spare time playing foosball, tennis table and football. Meanwhile, the IRC will continue to work tirelessly to ensure Samir gets the support and services he needs.

The IRC’s child protection team works in partnership with the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

*Names changed for privacy reasons