African nations struggle for independence

Armed with a new, global mandate, the IRC came to the aid of a continent struggling to transition to independence.

Armed with a new, global mandate, the IRC came to the aid of a continent struggling to transition to independence.

In just a few years on either side of 1960, a wave of struggles for independence was sweeping across Africa. Between March 1957, when Ghana declared independence from Great Britain, and July 1962, when Algeria wrested independence from France after a bloody war, 24 African nations freed themselves from their former colonial masters.

In most former English and French colonies, independence came relatively peacefully. But the transition from colonial governments did not always lead to peace. Internal conflicts within the newly independent countries and the continued resistance of the colonial powers in southern Africa often forced large numbers of innocent people to flee civil strife and repressive new regimes.

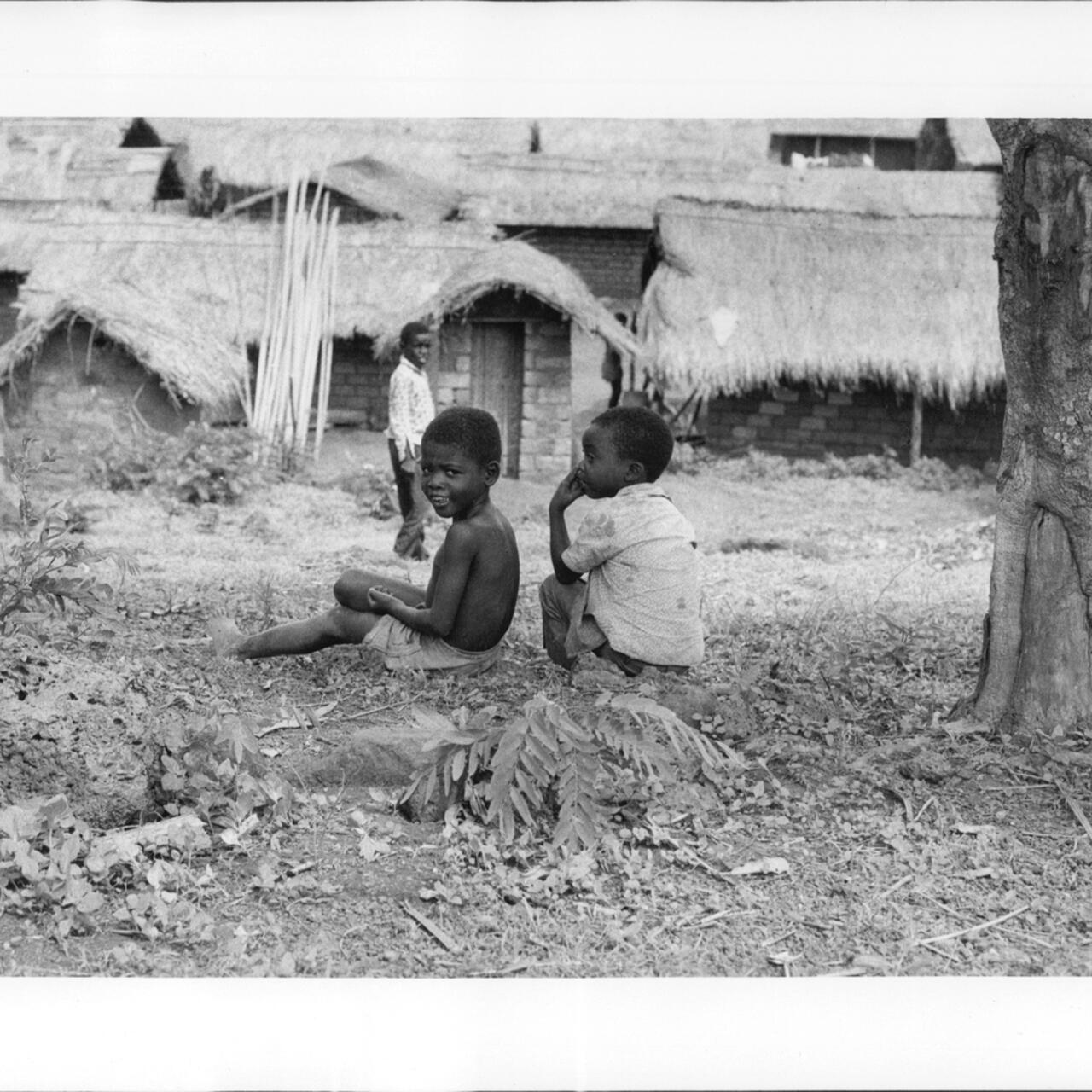

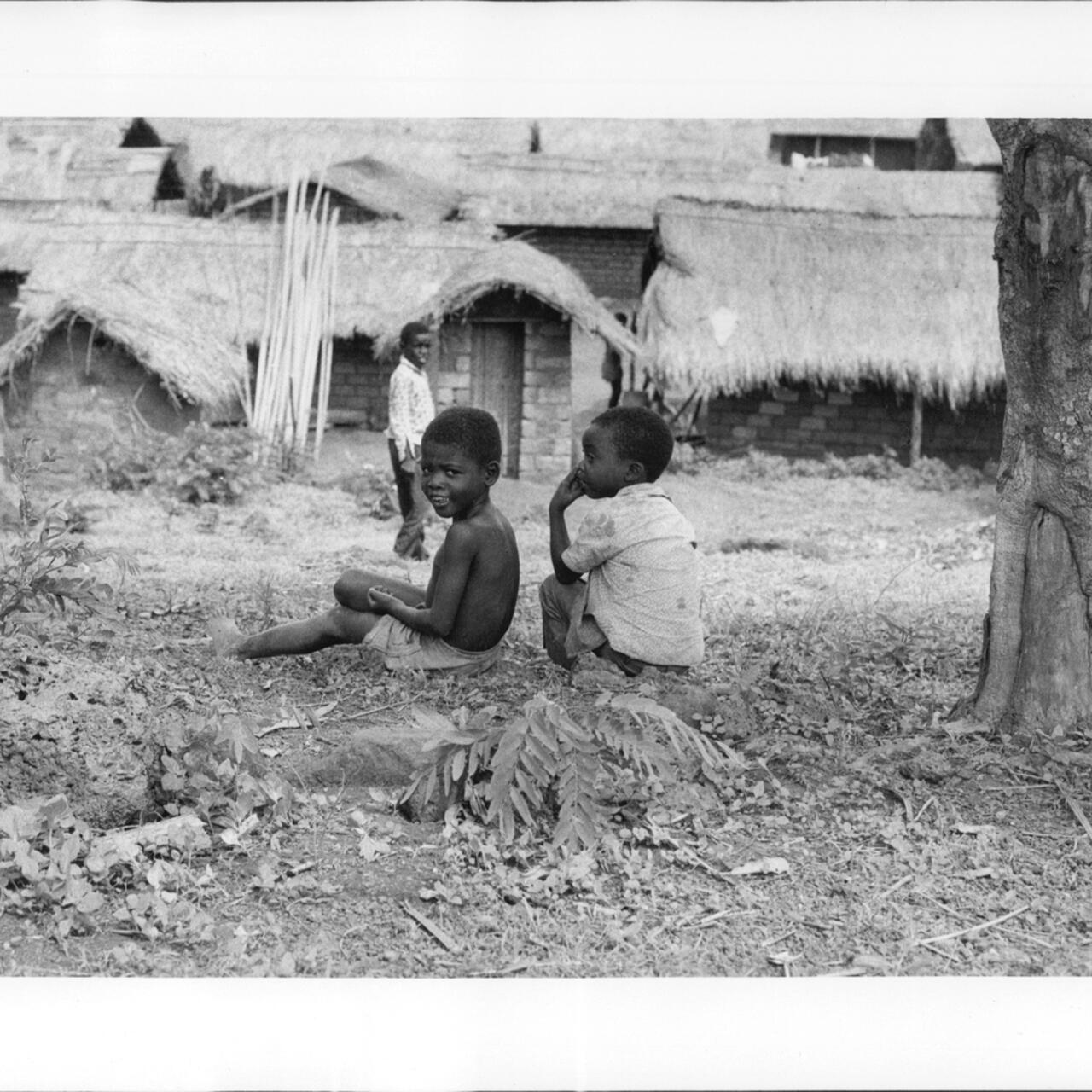

When more than 200,000 Angolans escaped their country’s Portuguese colonial government and fled to nearby Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 1962, the IRC responded quickly. This was the IRC’s first initiative on the African continent and a demonstration of the organization’s expanded global mission and responsibility. We supplied medicine and enlisted refugee doctors for a medical assistance program. Dr. Marcus Wooley, a French-speaking surgeon who had himself once been a refugee from Haiti, was sent to Zaire. He administered the distribution of medical supplies, performed surgery at the Service d’Assistance aux Refugies Angolais clinic and at the many border camps he visited. He devoted much of his time to teaching first aid and preventive care to the refugees and to improving the skills of Angolan health care workers. Working with Catholic Relief Services and Church World Service, the IRC was able to send $179,000 worth of medicines, high-protein food and other aid to Angolan refugees. After 18 months, the IRC was forced to withdraw, along with United Nations troops, owing to renewed fighting between insurgents and government forces. Fortunately, local aid workers were able to take over the programs.

In 1967, the IRC became involved in a dramatic crisis in Nigeria. After winning independence from Britain in 1960, Nigeria formed a coalition government that was soon roiled by a disputed election, massacres of Ibo people, and the eventual secession of the Ibos, who claimed the southeastern part of Nigeria as the independent nation of Biafra. Civil war and mass starvation followed. The IRC joined with other organizations in launching the Biafra Christmas Ship, which provided 3,000 tons of food, drugs, and other life-saving supplies to the Ibos. We also recruited Nigerian doctors in the U.S for volunteer missions to Biafra. At first it seemed that Biafra might survive. But famine and Nigeria’s superior army overcame the struggle for independence. The Ibos surrendered in 1970, but not before an estimated one million people had died.

The magnitude of the crisis in Biafra captured the world’s attention. But other conflicts on the African continent were hardly noticed by the general public. An IRC report presciently predicted where much of the organization’s energies would be directed in the years to come:

Refugee problems in Africa will undoubtedly multiply and intensify as the result of the complex tribal, religious, racial, national, and political conflicts. Biafra is an extreme example, but it would be unrealistic not to expect more crises . . . IRC’s commitment to the refugee cause will require a deepening of its involvement in Africa.

Many more crises have developed, and the IRC has indeed deepened our involvement in Africa, even as we have continued to pursue our core purpose of helping uprooted people to move from harm to home.

This post written by International Rescue Committee president George Rupp in honor of the organization’s 75th anniversary was first published on May 30, 2008.