The Lost Boys of Sudan

Over 25 years ago, Sudan’s civil war uprooted 20,000 Sudanese children. They were known as the Lost Boys.

Over 25 years ago, Sudan’s civil war uprooted 20,000 Sudanese children. They were known as the Lost Boys.

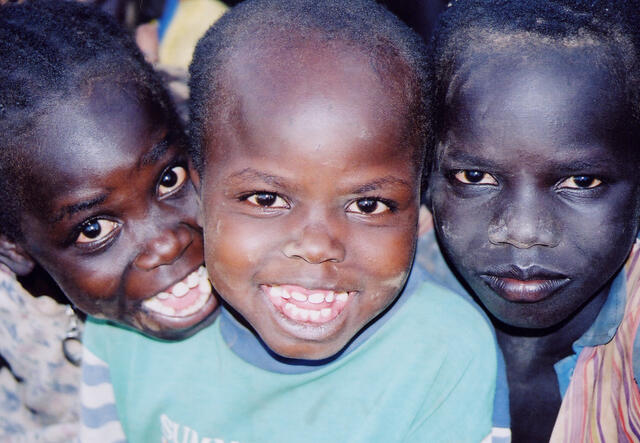

In 1987, civil war drove an estimated 20,000 young boys from their families and villages in southern Sudan. Most just six or seven years old, they fled to Ethiopia to escape death or induction into the northern army. They walked more than a thousand miles, half of them dying before reaching Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. The survivors of this tragic exodus became known as the Lost Boys of Sudan.

In 2001, close to four thousand Lost Boys came to the United States seeking peace, freedom and education. The International Rescue Committee helped hundreds of them to start new lives in cities across the country.

The outbreak of civil war in Sudan in 1983 brought with it circumstances that would permanently alter the lives of thousands of Sudanese boys and young men. As forces of the government of northern Sudan resumed its campaign against the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the southern-based rebel group began inducting boys into the movement.

In the next few years, an estimated 20,000 Sudanese children fled their homeland in search of safety in what turned out to be a treacherous 1,000-mile journey to Ethiopia.

Wandering in and out of war zones, these "Lost Boys" spent the next four years in dire conditions. Thousands of boys lost their lives to hunger, dehydration, and exhaustion. Some were attacked and killed by wild animals; others drowned crossing rivers and many were caught in the crossfire of fighting forces.

In 1991, war in Ethiopia sent the young refugees fleeing again and approximately a year later they began trickling into northern Kenya. Some 10,000 boys, between the ages of eight and 18, eventually made it to the Kakuma refugee camp—a sprawling, parched settlement of mud huts where they would live for the next eight years under the care of refugee relief organisations like the IRC.

The IRC began working in Kakuma in 1992 to assist the Lost Boys and other refugees fleeing the fighting in Sudan. Its programmes expanded over time to include all of the camp’s health services: treating refugees who arrived malnourished or ill, offering rehabilitation programs for those who were disabled, and working to prevent outbreaks of disease.

Older boys took part in IRC education programmes, and received support to learn trades and start small businesses to earn money to supplement relief rations. The IRC also helped these young entrepreneurs start savings accounts and access small loans to invest in their futures.

“The IRC’s health, sanitation, community services and education programs touched, in one way or another, the lives of all the Lost Boys who were in Kakuma and who were eventually resettled in the U.S.A.,” recalled Jason Phillips, who managed IRC programmes in the camp from 2000 to 2001. “We accompanied and supported them throughout a large part of their journey.”

As the war in Sudan continued to rage, the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) determined that repatriation and family reunification was no longer an option for the Lost Boys. UNHCR recommended approximately 3,600 of them for resettlement in the United States and the U.S. State Department concurred.

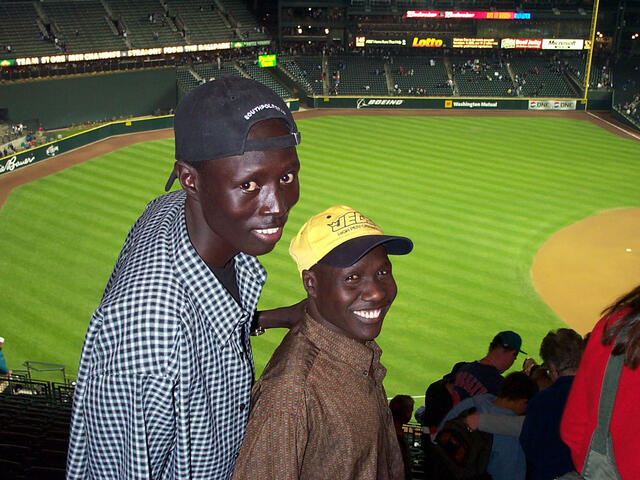

The Kakuma youth began arriving in the U.S. in small groups in the fall of 2000. Over the next year the IRC helped hundreds resettle in and around Atlanta, Boston, Dallas, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, San Diego, Seattle and Tucson.

Because many of the newly arrived Lost Boys were over 18 and considered adults, they were not placed into foster care. "We place the older boys together in apartments to try to maintain the kind of support network that they developed throughout their difficult journey and while living in the Kakuma camp," said Jon Merrill, who was then director of the IRC's resettlement programme in Tucson. "They have been like family to each other for so long now, so it's best for them to continue to live as a family unit here."

Most of the older boys who came to the United States were eager to capitalise on opportunities for higher education, but found that their idea of becoming full time students was not a realistic goal. Since most were over 18 and living on their own they needed to support themselves. And even though the majority attended school within Kakuma camp and had completed or were well on their way to completing high school, they did not necessarily qualify for entry into U.S. colleges. For these young men, IRC staff members stressed the importance of finding a job soon after arrival, and continuing their educational pursuits part-time.

The IRC helped the Lost Boys find jobs with local employers and connected them with volunteer mentors for help studying for exams to enable them to receive a General Equivalency Diploma (GED), and in turn, apply for college.

The Lost Boys faced enormous challenges in adjusting to American culture and modern society. IRC case workers worked closely with the boys in orienting them to their new communities, making sure that they were as comfortable as possible, and offering guidance on such issues as personal safety, social customs, public transportation, shopping, cooking, nutrition and hygiene.

Volunteers, many of whom became aware of the immense needs of this group through media coverage, also played a significant role in this area. They served as an essential link to the greater community, helping to generate additional employment opportunities, as well as increase donations and awareness.

Volunteers at the IRC's Boston office (now closed) took part in a mentoring programme for newly arrived Kakuma youth, providing support and guidance, and organising recreational activities to bring the young men together.

Many of the Lost Boys resettled by the IRC also took part in IRC programmes aimed at helping them cope with their traumatic past and easing their transition into such a different culture. The IRC's Phoenix resettlement office, for example, worked with clinical psychologists to provide specialised counselling services.

Over the next decade the Lost Boys built new lives for themselves in their adopted country. Many of them went on to earn college degrees and attain U.S. citizenship, while wondering whether they would someday have the opportunity to return to their homeland and reunite with the families they left behind.

Then, in 2005, news came that gave them hope: a peace agreement had been signed between North and South. The civil war, which had claimed more than two million lives, was over.

The tenuous peace held, and in 2011 southern Sudan held a referendum in which its people almost unanimously decided to secede from Sudan and form a new nation.

Some of the Lost Boys were among the many thousands of South Sudanese refugees who streamed home during these optimistic years. They were eager to use their education to help build the world’s newest independent country. One of them, Abraham Awolich, told The New York Times: “I don’t want to see another generation of children go through what I’ve gone through and what other children of my generation went through.”

In December 2013, political tensions between factions loyal to President Salva Kiir and opposition leader Riek Machar erupted into fighting in South Sudan's capital, Juba. Since then thousands of people have been killed and more than a million forced to flee their homes.

The fighting put an end to three years of peace and a shaky stability following South Sudan’s declaration of independence from Sudan. Now South Sudan is facing a humanitarian catastrophe and an upsurge of violence between ethnic groups. Many of the Lost Boys who fled civil war two decades ago have returned home only to find a new war.

Learn how you can help refugees in the U.S. and around the world.