How a simple tape measure helps tackle child hunger

When applied properly, simplified approaches to diagnosing and treating malnutrition result in recovery more than 90% of the time—all while saving 21% on costs.

When applied properly, simplified approaches to diagnosing and treating malnutrition result in recovery more than 90% of the time—all while saving 21% on costs.

Malnutrition in children is treatable, yet up to 2 million children die each year, and less than 1 in 5 children impacted by life-threatening acute malnutrition receive the care they need.

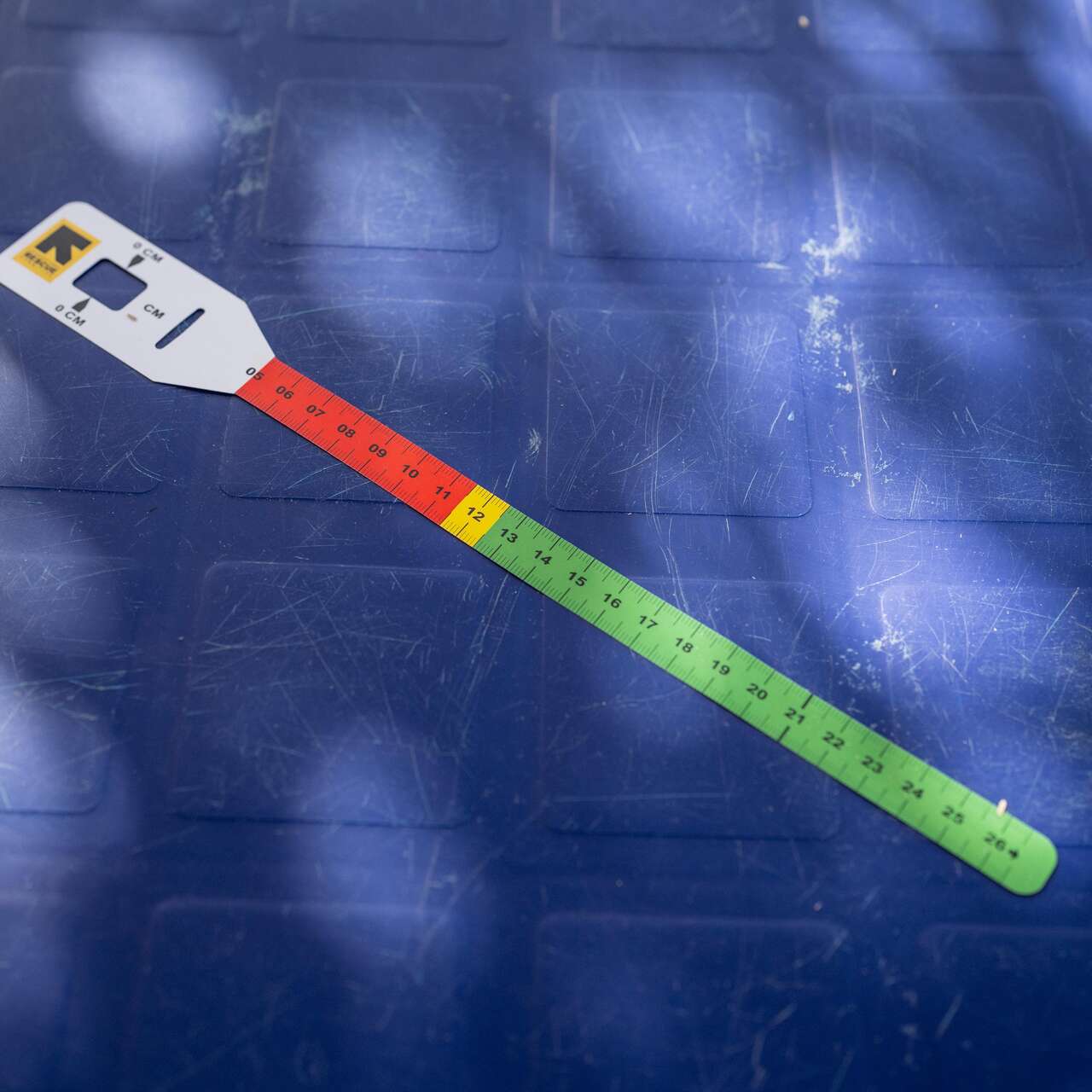

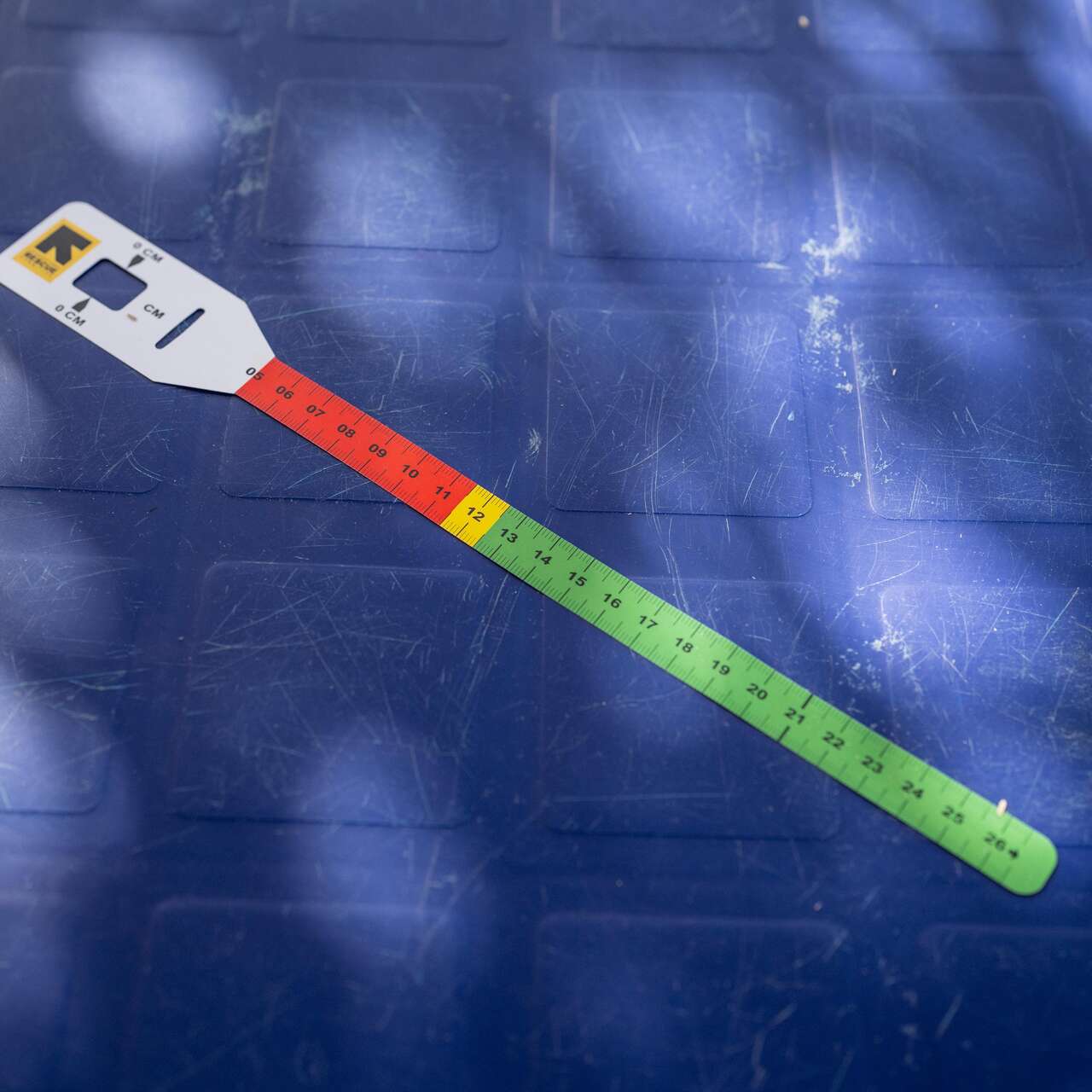

This easy-to-use, color-coded tape measure could be the key to solving the problem.

Studies show that using a simpler approach to diagnosing and treating malnutrition helps more than 90% of children treated with these approaches recover. What’s more, this approach to treatment is more accessible and can be used in hard-to-reach places without health facilities – all while saving 21% on costs.

A malnourished child is not eating enough nutritious food to grow, develop healthily, and maintain a healthy immune system. As their bodies weaken from a lack of nutrition, they become more vulnerable to other diseases. They are 11 times more likely to die than healthy children.

Technically speaking, malnutrition is not the same as hunger. Hunger is the physical sensation caused by a lack of food, while malnutrition refers to nutritional deficiencies such as lack of protein or energy. These two challenges are closely related.

Even if a child survives an experience of acute malnutrition, they often face long-lasting harmful effects– impacting their physical and cognitive development, especially in children under the age of five who are in a critical period of growth.

The current systems used to treat malnutrition divide cases into two categories: severe and moderate. Each group is given a different treatment and diagnosis process. This is needlessly complicated and leads to confusion and the squandering of precious resources.

For example, children with ‘moderate’ acute malnutrition are not provided with nutrient-rich peanut paste called RUTF – despite this being a recognised “miracle cure” for acute malnutrition. This can mean they have to wait until their condition deteriorates before accessing this treatment.

By removing the distinction between severe and moderate cases of acute malnutrition, simplified approaches for the diagnosis and treatment can reduce blockers to accessing treatment.

MUAC (mid-upper arm circumference) tape is a tried-and-tested way to diagnose malnutrition in children. This simple colour-coded tape is used by health workers to assess malnutrition in children. However, it can also be used at home by parents checking their children, or by community health workers – reducing the need to travel to health clinics and further improving scalability of the simplified approach.

RUTF paste (‘Ready To Use Therapeutic Food’) is a fortified peanut paste invented in 1965 by French paediatrician Andre Briend. It is high in calories, nutrients, and vitamins and helps children suffering from malnutrition gain weight and recover. It can be eaten by young children not yet ready for solids, is easy to transport, and is non-perishable.

RUTF has been called a “miracle cure” for malnutrition but is typically only offered to severe cases. This creates a situation whereby children must wait until they are diagnosed as severe before they can get this treatment.

The IRC has developed an easy-to-follow dosage system covering both severe and moderate cases of acute malnutrition.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) helps people whose lives have been shattered by conflict and disaster to survive, recover and rebuild.

Founded in 1933 at the call of Albert Einstein, we now work in over 40 crisis-affected countries as well as communities throughout Europe and the Americas.