Diala Brisly is an artist, activist and refugee. Forced to flee Syria in 2013 and now resettled in France, Diala uses her art both to confront her own trauma and to defend the human rights of others. This commitment has led her to create work supporting a women’s hunger strike in Syria and to host artistic workshops in refugee camps. Today, she runs art therapy workshops for children affected by war.

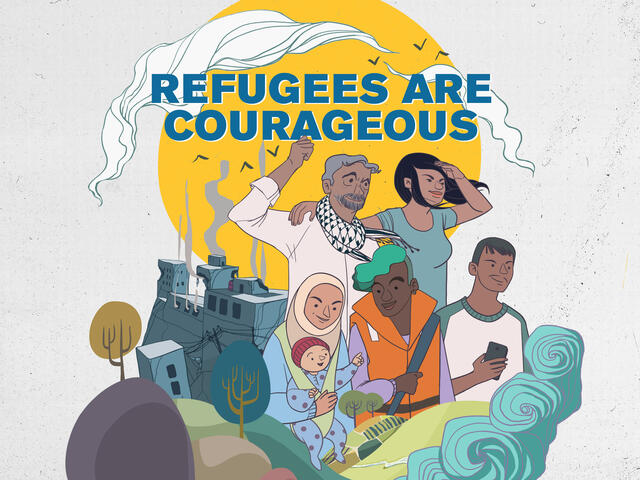

Diala’s newly commissioned illustration, which makes the statement “Refugees are Courageous,” kicks off the International Rescue Committee’s 2021 World Refugee Day campaign honouring and celebrating the contributions of refugee artists. Below, Diala explains how the illustration came about and what courage means to her.

For me, courage is having fears, having all this worry, having all this trauma, and still having the energy to keep going.

I'm really happy to be part of the IRC's World Refugee Day campaign this year. The slogan is “Refugees are courageous.” I really like the slogan because it shows strength, regardless of all the troubles that we are going through.

Being strong doesn't mean not being vulnerable. It's being vulnerable, but not letting it stop you from going on. This is courage.

In my illustration for the IRC, there are men and women of different ages and cultures. And there is a character presented as LGBTQ, and there is a child. It's very important to show solidarity among refugees. I believe in solidarity between all people. When we have this struggle in common, and we understand each other's pain, we are able to help each other because we share similar experiences.

One of the characters in the illustration is wearing a life jacket. For me, a life jacket is symbolic. The media puts the spotlight on refugees when they are in the middle of the sea. But it’s very important to understand that the crisis didn't start in the Mediterranean, it started before.

From comics to commitment

I grew up in Kuwait, and then I moved to Syria with my family when I was 10. I started doing animation for the Syrian channel, “Spacetoon.” I went on to be a freelancer, doing comics, illustration books and children's magazines.

When the uprising started in Syria we were really very excited to see change. We lived this romantic dream—until we realised that we were really limited, and once we tried to protest, the response was violent. In 2012, I did my first illustration about what was happening. I didn't think it would be very powerful. I did it because I was suffocating, it was kind of a way to breathe, to express what was happening. Journalists started sharing my drawings to supplement their reports. So this encouraged me to do more political art.

During the war in Syria, I was responsible for delivering medical supplies secretly in my car. More and more checkpoints were appearing. It became very dangerous. A lot of my colleagues who worked in hospitals and organised protests disappeared or got arrested. Some of them had to leave because they were on a blacklist.

I was really very lucky to not be arrested. In the last few months, I thought this delivery would be the last. Eventually, I was reported, but for some reason, they didn't come for me. So that was the moment I realised I couldn’t stay in Syria anymore. We didn’t feel like we were making any progress and at the time many of us felt disappointed. A lot of people stayed there. I consider them very courageous and brave to keep going.

When I left for Istanbul, I thought I would stay for a few months and go back, like many Syrians thought. Then a few months became a year. And we started realising the war was not going to end soon.

In Istanbul, I struggled to learn the language and find a job. I was totally isolated. I became more addicted to the news, reading about what was happening in Syria. I used to draw about it. During this time, I lost my brother to the war. This was a really big shock for me, even though I expected it. No matter how prepared you are, it doesn't help. That really changed my life.

From commitment to connection

I went to Lebanon to visit my friends and also to visit the camps where refugees are living. At one of the camps, I met a girl who was also an activist in Syria. She was planning to open a public library in one of the camps. I told her I could help because I worked with publishers in Lebanon. I also offered to create a mural in the library. I decided to move to Lebanon—here I could participate, do something more than just sitting at home isolated.

When I painted my first mural, I saw the impact it had on the kids. They really loved it. And they were very curious. This small audience's reaction encouraged me to do more murals.

I started running art therapy workshops. A lot of the kids saw their close friends, their siblings dying in front of them in a very ugly way. So I realised how important it is to use art to empty out all this terror we have inside.

When I arrived in Europe, I didn't expect I would have difficulties. I thought there might be some procedures but if you are just open minded enough you’d be ok. In reality, there are huge cultural differences and also the language barrier. There are many things I appreciate here, but also many things I miss from my own culture.

In my journey with art, I am learning more and more how everything is inspiring. Tragedy is inspiring, happy moments are inspiring but you don’t need extraordinary situations to be inspired. When you open your eyes, you find inspiration everywhere.

You don't need to be an artist to use art to connect with others or with yourself. It's just the freedom of putting some colors on papers—this is really enough to feel the connection, without having the frustration of perfection

Seeing my artwork going around the world surprises me. I hope it will have an impact on the people who see it. Maybe it will change the stereotype of refugees.

Diala Brisly is part of the agency of artists in exile, which supports and elevates refugee artists in France.