Increasingly restrictive border policies have created the most dangerous route in the world. The coronavirus pandemic has made it even worse.

The Central Mediterranean Route runs from sub-saharan Africa through the deserts of Niger, to conflict-ridden Libya and across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy. It’s been named the most perilous migration route in the world by the Institute of Migration as people are forced into destitution by smugglers and risk dying while crossing the desert or drowning in the sea. Read more about the route.

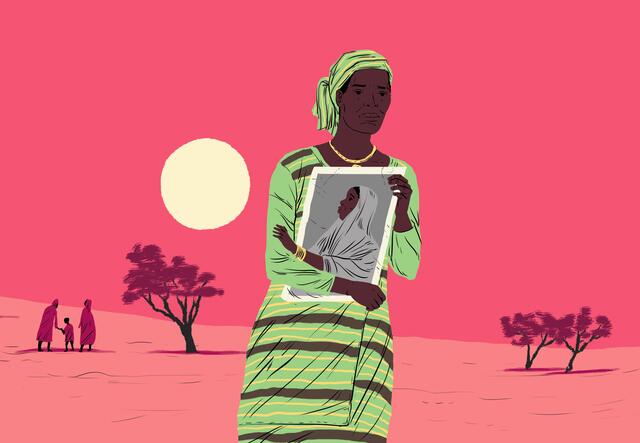

Illustrations by Paul Blow.

COVID restricts movement

Since COVID-19 took hold, the situation has become even tougher for those seeking protection and better lives. The IRC has found that 83% of conflict-affected countries we operate in have implemented additional border restrictions due to the pandemic. Movement restrictions come with a great risk for those fleeing conflict and persecution or seeking better lives, who find themselves trapped at borders and prevented from seeking asylum.

27-year old Asim*, from Sudan told us that he attempted to cross the Mediterranean but was turned back to the shores of Libya as the borders had tightened since the pandemic. “The corona pandemic had a huge effect on migrants in Libya. Migrants don’t have what they need to sustain themselves tomorrow. Since the imposed curfew, things have come to a grinding halt, there is no one to support.”

More than 80% of the migrants and refugees interviewed by the Mixed Migration Center in Libya affirmed that the pandemic had impacted upon their movement. They reported being constrained both within the country they had arrived in and across international borders. These measures increase their risk of detention and deportation, and interrupt their resettlement process.

Some people on the route are desperate to return home and be with their families. 27-year-old Marie is trying to get back to Cameroon. She’s currently living in Niger, but was attacked and robbed and is now sleeping on the streets with no way to earn money. “I don't have enough money to travel back. I really miss my family. I don’t know when I will be able to go back because of the coronavirus - it’s disturbing everything.”

I don’t know when I will be able to go back because of the coronavirus - it’s disturbing everything.

People on the move are trying to protect themselves against the virus. In all the countries where we work, they’ve reached out to our medical teams to get advice on preventive measures against the virus.

Daily wages drying up

Along the route, people rely on daily wages in unstable jobs just to be able to buy food and basic necessities. The pandemic has forced people into lockdowns and cut off work opportunities with no savings. This has impacted their ability to cover their basic needs, to afford potential onward travel, and to send home money to their families.

Jidda, who is from Nigeria and is living in Rome in a government shelter with other migrants and refugees, has lost the bits of work he could find in the city. “It’s a bit tough because most of us, we have families at home that look up to us, we used to do menial jobs but now there is nothing like that, it’s really terrible,” he says.

We used to do menial jobs but now there is nothing like that.

He also struggles with the lack of freedom that comes with living in the shelter, which provides three meals a day at set times. “They don’t allow you to cook and if you decide to leave the place for three days if you get work, you’re automatically evicted. Everybody is complaining, they have no money. We are fortunate enough to still be here, whether the food is good or not, you just have to manage, you have a place to lay your head.”

*Names have been changed for protection throughout.

Our response

Along the route, the IRC, Danish Refugee Council (DRC), the Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) and Start Network have formed The Mediterranean Mixed Migration Consortium to help people on the move. In Libya, our work ranges from helping people to recover from trauma with a dedicated team of psychologists, to providing shelters for migrants without homes. In Niger, our social workers provide legal aid and enable people to call home for free. We're also providing cash to vulnerable people, particularly women, which enables people to buy food and other essentials with dignity and choice. In Italy, the IRC operates Refugee.Info, an online platform that answers questions from refugees and migrants who have arrived in the country. The service helps people navigate their new surroundings and understand the asylum process. The DRC started operate mobile units to reach vulnerable people living in the street who have lost access to food, health assistance and shelter during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The MMC is a knowledge centre offering independent and high-quality data, research, analysis and expertise on mixed migration. The information from MMC is invaluable in providing rapid analysis of the context on the route. Start Network provide an emergency fund to respond to new and unforeseen needs on the route, which has helped more than 45,000 people since August 2018.

The Mediterranean Mixed Migration Consortium is funded by DFID to assist refugees and migrants across West and North Africa.