The top 10 crises the world can’t ignore in 2023

Learn about the world’s worst crises and what can be done to help.

Learn about the world’s worst crises and what can be done to help.

Each year, the International Rescue Committee releases a list of the 20 humanitarian crises expected to deteriorate the most over the next year. For the past decade, this report has helped us determine where to focus our emergency services and lifesaving support to make the greatest impact.

Go to the latest Emergency Watchlist 2024

Heading into 2023, countries across the globe continue to struggle with decades-long conflicts, economic turmoil, and the devastating effects of climate change. The guardrails that once prevented such crises from spiraling out of control—including peace treaties, humanitarian aid, and accountability for violations of international law—have been weakened or dismantled.

The human and economic costs of these crises and disasters are not equally shared. The countries on the 2023 Watchlist are home to just 13 percent of the global population, yet they account for 90 percent of people in humanitarian need and 81 percent of the people who have been forcibly displaced.

If we can understand what is happening in these 20 countries—and what to do about it—then we may, finally, have a chance to start reducing the scale of human suffering.

Here, we break down what you need to know about the 10 countries likely to face the worst humanitarian crises next year. For more information and to see the full list of 20, read the 2023 Emergency Watchlist report or our Watchlist at a Glance summary.

The war in Ukraine has sparked the world’s fastest, largest displacement crisis in decades, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), pushing the country into the Watchlist for the first time since 2017. Many still in the country are facing winter without access to food, water, health care, and other essential supplies. The conflict also continues to have ripple effects across the world.

Ukraine is not higher on the Watchlist only because the huge scale of the international response helped to mitigate the impact of the war, at least somewhat, relative to other Watchlist countries.

Conflict is likely to continue into 2023, with Ukrainians facing increased risk of injury, illness and death. Russian missile strikes could leave millions without water, electricity and heating in winter. 6.5 million Ukrainians have been displaced inside the country, while more than 7.8 million are refugees across Europe.

The IRC launched an emergency response to the war in February 2022, working with local partners in Ukraine, Poland and Moldova to reach the most vulnerable by providing essential items, cash assistance, improved access to health care, and safe spaces for women and children.

Haiti makes it into the Watchlist top 10 as political instability and gang violence surge following the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in 2021.

Armed gangs regularly take control of distribution routes, causing shortages of basic goods and fuel. Rising prices make it increasingly difficult for people to afford to buy the food they can access.

Meanwhile climate shocks and the first cholera outbreak in three years strain critical health and sanitation systems.

Gang violence will continue to disrupt people’s livelihoods and essential services. Kidnappings, rape and killings are all rising, putting thousands at risk of death.

Haiti also recorded record levels of food insecurity in 2022, which is expected to worsen in 2023.

Humanitarian actors and other service providers will continue to face disruptions to their work in 2023, preventing aid from reaching those most affected.

While the IRC is not currently present in Haiti, we have a history of supporting the country dating back to 2010, working with a strong network of local civil society organisations to respond to the needs of communities. We currently serve Haitians on the move in countries where the IRC has a programmatic response, including Mexico.

The situation in Burkina Faso grows increasingly dire as armed groups intensify their attacks and seize land. Tensions among the country’s political factions have contributed to the instability. Members of the armed forces seized power twice in 2022 alone.

A growth in the number of vigilante groups has added to the violence. Further expansion among these groups could increase political instability.

Armed groups now control as much as 40 percent of the country.

While needs are dire, humanitarian aid is limited by conflict and lack of funding. Some towns in northern Burkina Faso are almost entirely cut off. The price of food has increased 30 percent, among the highest food inflation rates in the world.

The IRC is active in Djibo, an area currently under siege by armed groups and host to many people who have fled their homes. We deliver clean water, sanitation services and primary health care programmes.

South Sudan is still recovering from a civil war that ended in 2018. While conflict has decreased, localised fighting remains widespread. The country is one of the most fragile in the world.

Climate disasters including severe floods and droughts make it increasingly difficult for people to access food and basic resources.

More South Sudanese people than ever before—7.8 million—will face crisis levels of food insecurity in 2023. Despite severe flooding, destroyed crops and disease outbreaks, funding shortages forced the World Food Programme to suspend part of its food aid in 2022.

Conflict across the country also threatens civilians and humanitarian supporters. South Sudan consistently has the world’s highest level of violence against aid workers, hindering their ability to reach people in need.

With more than 900 full-time staff in South Sudan, the IRC's work includes lifesaving health and nutrition, protection and economic recovery services.

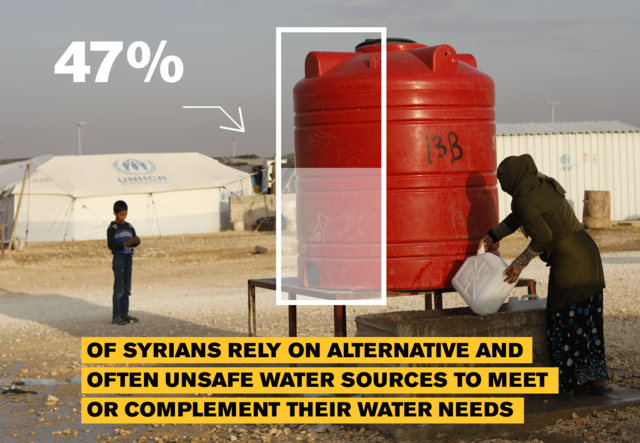

Over a decade of war has destroyed Syria’s health system and left the country on the brink of economic collapse. A decade of conflict in neighbouring Lebanon has further increased food prices and poverty. Currently, 75 percent of Syrians are unable to meet their most basic needs and millions rely on humanitarian aid.

Prices of goods will continue to increase into 2023. Ongoing conflict and airstrikes could force more people to flee their homes.

The first cholera outbreak in a decade threatens to overwhelm Syria’s health care and water systems.

Since 2014, the U.N. Security Council has authorized U.N. agencies to deliver aid from neighbouring countries into Syria. This critical lifeline could be cut off for millions in early 2023—in the middle of winter when needs will be particularly severe.

The IRC promotes economic recovery with job training, apprenticeships and small business support. We also support health facilities and mobile health teams with lifesaving trauma services as well as primary, reproductive and mental health services.

The crisis in Yemen is deepening as an eight-year conflict between armed groups and government forces remains unresolved. While a ceasefire reduced fighting for several months, it collapsed in October 2022 and failed to mitigate the economic and health consequences of conflict.

Humanitarian funding has lagged. As it stands, 80 per cent of the population lives in extreme poverty and 2.2 million children are acutely malnourished.

Due to the failed truce, major conflict could resume in 2023. Yemen is at increased risk of violence unless a longer ceasefire agreement is reached.

Already, localised fighting persists, making it difficult for humanitarian organisations to deliver aid to the most vulnerable. Basic goods like food and fuel will remain unaffordable for many Yemenis.

While ongoing conflict and restrictions have posed a challenge, the IRC and our volunteers continue to reach vulnerable people and provide health care, women’s protection and empowerment, and education programming.

Over 100 armed groups fight for control in eastern Congo, fueling a crisis that has lasted for decades. Citizens are often targeted. After nearly 10 years of dormancy, the M23 armed group launched a new offensive in 2022, forcing families to flee their homes and disrupting humanitarian aid.

Major disease outbreaks–including measles, malaria and Ebola–continue to threaten an already weak health care system, putting many lives at risk.

Conflict remains the key concern in Congo, especially as tensions escalate and M23 takes control of more land.

Political unrest is rising as the country prepares for elections. Leaders have been accused of inciting and supporting conflict to win over constituents. Despite peacekeeping efforts, violence against aid organizations may increase before the vote.

The IRC works with communities on peace-building projects to reduce conflict and launches emergency responses to contain Ebola and other health crises, including the latest outbreak in eastern Congo.

Afghanistan ranked No. 1 on the 2022 Watchlist but dropped down for 2023—not because conditions have improved but because the situation in East Africa is so severe.

Over a year since the shift in power, Afghans remain in economic collapse. While a rapid increase in aid prevented famine last winter, the root cause of the crisis persists. Ongoing efforts to engage the government and improve the economy have fallen short. Almost the entire population is now living in poverty and preparing for another long winter.

Heading into winter, millions of people are unable to afford basic needs, with drought and flooding decimating crops and livestock.

Afghan women and girls will experience the brunt of this hardship. They remain at risk of violence and exploitation. And many are left without a voice as the government places bans on education, dress, travel and political participation for women.

The IRC more than quadrupled our staff in Afghanistan in 2022 to operate in 12 provinces, support 68 health facilities and manage 30 mobile health teams. In the next year, we expect to reach 800,000 people directly and impact 4 million with our services.

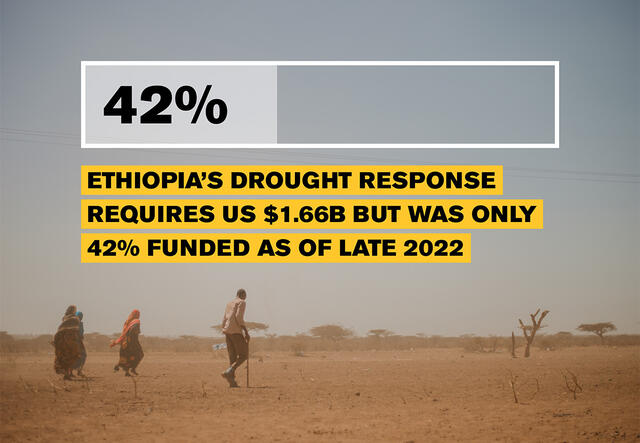

Ethiopia is heading toward its sixth consecutive failed rainy season, which could prolong a drought already affecting 24 million people. At the same time, various conflicts across the country are disrupting lives and preventing humanitarian organisations from delivering aid.

While a November 2022 peace deal may hold and offers hope for an end to the conflict in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, 28.6 million remain in need of humanitarian aid.

The humanitarian response to the drought in Ethiopia is insufficiently funded, even more so than in East African countries facing a similar crisis. If humanitarian groups can’t deliver resources in a country that is badly affected by aid funding shortfalls, Ethiopians will starve as they are hit by drought and rising food prices.

If the peace deal unravels, humanitarian needs will increase even more.

The IRC distributes cash and basic emergency supplies, builds safe water supply systems and sanitation facilities, and supports government partners and community workers in maintaining health clinics.

Topping the Watchlist for the first time, Somalia is facing an unprecedented drought and hunger crisis. People have already lost their lives to starvation, and the country is on the brink of famine.

This is no “natural disaster.” Human-caused climate change has increased the frequency and severity of droughts. Decades of conflict have eroded Somalia’s ability to respond to shocks of any kind, destroying systems and infrastructure that would have provided a guardrail against the current crisis.

For instance, with its food production decimated by climate change and conflict, Somalia’s dependence on imports has proven disastrous—over 90% of its wheat comes from Russia and Ukraine.

Somalia, like Ethiopia, could experience its sixth consecutive failed rainy season in 2023. High global food prices driven by the war in Ukraine make it even harder for families to eat.

Humanitarian organisations have limited ability to reach people in areas controlled by non-state armed groups. There are even reports of one group destroying food deliveries and poisoning water sources.

Meanwhile, the humanitarian response in Somalia remains severely underfunded.

The IRC has been operational in Somalia since 1981, with programs including health, nutrition, water and sanitation services; women’s protection and empowerment; and cash assistance. We are scaling up our programmes to address drought and rising food insecurity, and we are expanding to new areas to meet severe needs.

Aid-as-usual will not address the severe challenges revealed by Watchlist. To make a lasting impact, international institutions must rethink the way we address crises in 2023. This involves setting ambitious goals to break ongoing cycles of conflict and devastation.

A record 340 million people are in need of humanitarian aid this year, and 100 million have been forced to flee their homes. Make a donation to support the IRC's life-changing work in Watchlist countries and across the world.