Varian Fry’s Holocaust rescue network and the origins of the IRC

In 1940 young journalist Varian Fry led a daring mission to help Jewish refugees and some of the Nazi’s most-wanted escape the Holocaust.

In 1940 young journalist Varian Fry led a daring mission to help Jewish refugees and some of the Nazi’s most-wanted escape the Holocaust.

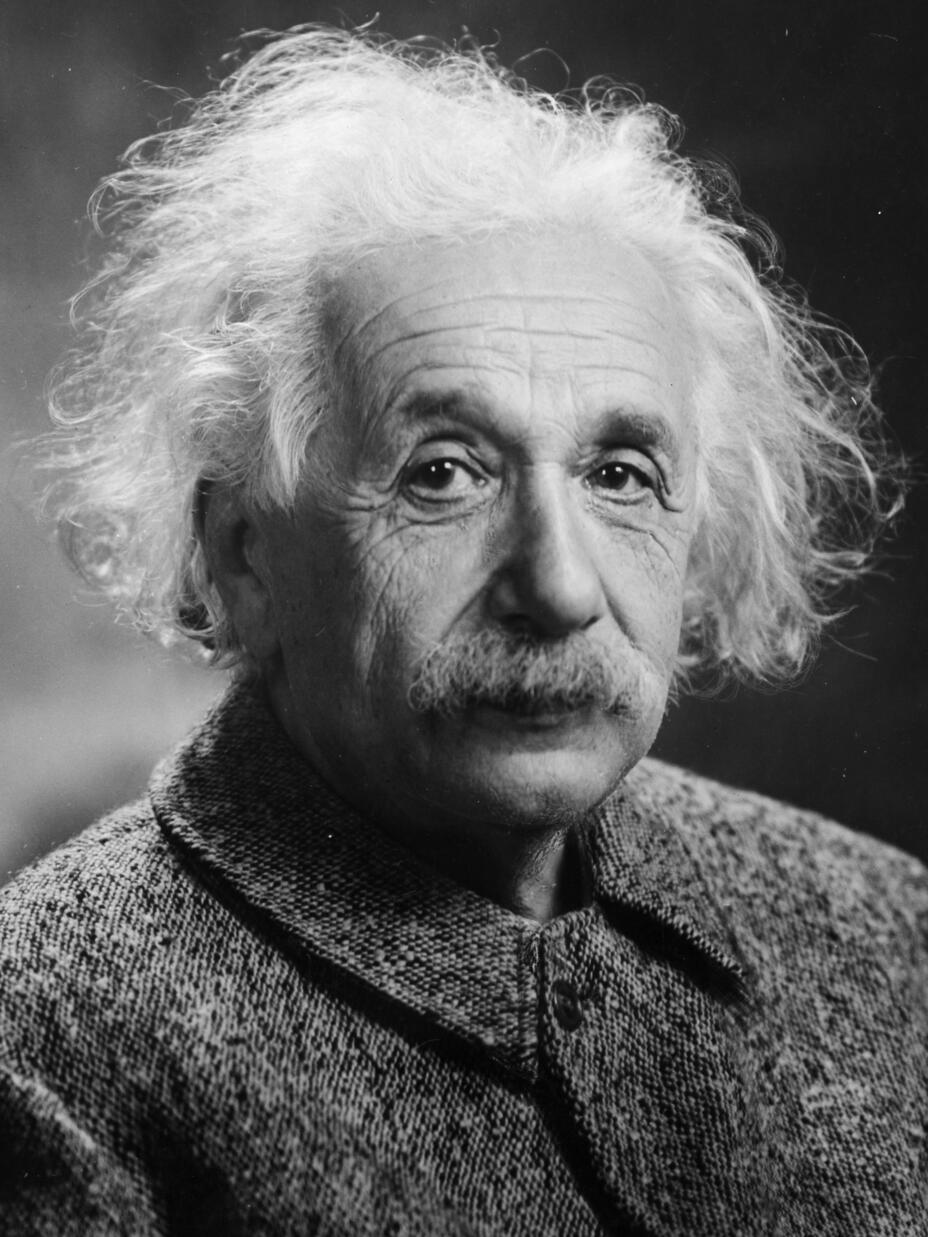

Back in 1933, Albert Einstein helped found the organization that became the International Rescue Committee, with the aim of helping people flee Nazi persecution. Later, during World War II, American journalist Varian Fry was instrumental in making an ambitious rescue operation happen.

These events have even inspired a new Netflix series, Transatlantic, which depicts the story of Varian Fry and his team’s work evacuating refugees from Vichy France.

How much do you know about the origins of the IRC?

In January 1933 Hitler rose to power as chancellor of Germany, and the Nazi takeover of the country was underway. The National Socialists banned opposing political parties and Germany’s labor unions, suspended civil liberties, and launched the purging of Jews, political opponents and other “undesirables” from the government and universities.

By July, the European-based International Relief Association (IRA), which had been co-founded by German-born physicist Albert Einstein, was forced to quit operations. Einstein was dismissed from his university post in Berlin and planned to resettle in the United States.

He quickly urged a committee of 51 prominent American intellectuals, artists, clergy and political leaders to form an American chapter of the organization. Their objectives: to save anti-Nazi leaders targeted by the Gestapo, and guide those in imminent danger to safety in free countries.

Among the group was the philosopher John Dewey, the writer John Dos Passos, and the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr.

Einstein arrived in America on October 17,1933, among the thousands of Jews fleeing persecution. The IRA established offices at 11 West 42nd Street, opposite Bryant Park and not far from the International Rescue Committee's current headquarters location.

Over the next few years, as Hitler’s forces continued to seize control of Europe, the committee’s mission expanded to “assist all those of whatever race or opinion, who are refugees or suffering within Germany today under the lash of the Nazi government.”

In June 1940, Paris fell to invading Nazi forces, creating a massive exodus of refugees to the south of France.

On August 4, a young editor named Varian Fry boarded a transatlantic flight from New York to German-occupied France to lead a daring rescue operation.

The mission was conceived by a new American group, the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), of which Fry was a founding member. The goal: to rescue Europe’s celebrated artists, writers, and intellectuals who had fled to the country, many of whom were on the Nazis’ most wanted list.

Fry arrived in Marseilles with $3,000 strapped to one leg and a list of 200 artists and intellectuals thought to be in particular danger. He quickly recognized that the number was much higher. At this time, there were no refugee programs or aid agencies to ensure the safety of refugees.

At the first hotel where he stayed, Fry met Dr. Frank Bohn, a representative of the American Federation of Labor and the Jewish Labor Committee, who was also in France to assist in evacuating refugees. Bohn briefed Fry on the situation in Marseille, helping him to plan out his work. He also met Albert Hirschman, a Jewish-German humanitarian and refugee, who became an integral part of the team, and Lena Fischmann, who became Fry’s secretary.

Over the next year and a half, Fry and his small team helped at least 1,500 refugees escape from France to Spain and provided support to more than 2,000 others. They helped people of all different faiths and national origins, including many who were Jewish, putting them in greater danger of Nazi capture and execution.

As Justus Rosenberg, the youngest member of Fry’s team, recalled: “I was running errands…but no ordinary errands. Errands to run with false papers, money, various documents to try to get the refugees who were trying to get somewhere out of occupied Germany.”

Among those spirited out of France were the artists Marc Chagall and Max Ernst, the philosopher Hannah Arendt, and Nobel Prize-winning medical researcher Otto Meyerhof.

The collaborationist Vichy French government learned of Fry’s efforts and expelled him in August 1941, “for helping Jews and anti-Nazis.” He ultimately returned to the U.S. where he continued to support refugees through advocacy, journalism and financially supported some refugees who were unable to leave Europe with his personal funds.

In June 1942, Vichy officials closed the ERC office, forcing remaining staff in France to go underground. Many of them joined the French resistance movement and saved hundreds of other people.

Back in New York, Fry loudly, but in the end futilely, tried to alert the world to what would come to be known as the Holocaust.

“There are things so horrible that decent men and women find them impossible to believe."

“There are things so horrible that decent men and women find them impossible to believe,” Fry wrote in The New Republic in December 1942. Of the Nazis, he warned, “Their ends are the enslavement and annihilation of the Jews . . . [and] after them, of all the non-German peoples of Europe, and if possible, the entire world.”

As the crisis in Europe deepened and millions of uprooted people were on the move, the IRA and ERC joined forces to provide the most effective assistance for refugees of all religions, races and nationalities. They became the International Rescue Committee,

Esteemed Russian-French artist Marc Chagall was one of the many people Fry’s network assisted to escape occupied France. Art critic Robert Hughes referred to him as "the quintessential Jewish artist of the twentieth century".

He is most famously known for his large-scale paintings, including part of the ceiling of the Paris Opéra. Chagall also produced stained-glass windows for the cathedrals of Reims and Metz as well as the Fraumünster in Zürich, the United Nations, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Jerusalem Windows in Israel.

In 1960, long-term IRC supporters, the Rockefeller family, inspired by Chagall’s stunning work and powerful personal story, commissioned him to create a stained-glass window at the Union Church of Pocantico Hills, New York.

The installation would serve as a memorial following the death of philanthropist John. D. Rockefeller Jr, who built the chapel. Chagall ended up creating not one, but nine breathtaking windows that adorn the unassuming country church.

In 1964, Varian Fry began work on a major fundraiser to benefit the International Rescue Committee. The idea was to sell a cache of prints by renowned refugee artists and friends, including Chagall. Five years later, 250 limited edition copies of the “Flight Portfolio” were sold to support the IRC’s humanitarian work.

For Fry, it was many years before he received much-deserved recognition. Five months before his death in 1967, France awarded him the French Legion of Honor. In 1996, Israel honored him posthumously, when he became the first American to receive its “Righteous Among Nations” medal.

In addition, on June 26, 2005, a large crowd of local residents and dignitaries in the town of Ridgewood, N.J., where Fry grew up, gathered to name a street after him.

Varian Fry’s guiding conviction, that every life has dignity and is worth saving, remains the foundation of the IRC.

Ninety years later the IRC continues to provide life-changing assistance to people around the world.

Learn more about the IRC's rich history.

Learn more about who the characters in Transatlantic are based on.